More people in the United States are struggling to find appointments with a primary care doctor or clinic for checkups and sick visits. In fact, 30% of adults and more than 12% of children do not have a usual source of care, the highest rates in a decade. To address these primary care workforce shortages and to help keep care more affordable, a growing number of states are engaged in efforts to strategically invest in primary care — a core component of a strong health system proven to keep populations healthier and promote more equitable access to care. Studies demonstrate that high-quality primary care leads to better health outcomes and longer lifespans; it also is more cost-effective.

But, while more than 35% of health care visits nationally are to primary care physicians, only about 5% of health spending goes toward primary care services. Additionally, primary care spending has been falling since 2018 and is much lower than that seen in other developed nations, including many that rank higher on health care outcomes than the United States. (See the Primary Care Scorecard Data Dashboard for national and state spending trends.) These findings led the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, in its 2021 primary care report, to call for public and private insurers to increase their spending on primary care.

Smart investments in primary care services, such as higher compensation for providers and steady prospective payments for primary care practices, could help attract and retain more primary care clinicians. So too could additional funding for nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and others delivering team-based care, which may alleviate physician burnout and result in high-quality care for patients.

Nearly 20 states have initiatives related to primary care expenditure, ranging from multipayer collaboratives to define and measure primary care spending to specified spending targets.

Given the absence of a national consensus on how to measure or increase all-payer investment in primary care, the state-led work has been foundational. It includes defining primary care services, measuring spending on those services as a percentage of total health spending, and, for some states, setting an annual spending target. State targets reflect local nuances and rely on available data to measure spending. As a result, state primary care provider and service definitions vary, as do the types of data they collect to track their progress. Additionally, states with primary care targets rely on different enforcement mechanisms —from voluntary disclosure to financial penalties — to ensure health plans meet them.

This series of profiles highlights five states that are in different stages of enacting and implementing primary care spending targets, including early planning and coalition building; active efforts to engage state policymakers; and implementation or revision of an enacted state policy. All five states — California, Connecticut, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and Virginia — are represented in the Primary Care Investment Network, composed of state agencies, policymakers, advocates, and other stakeholders in nearly 30 states and supported by The Commonwealth Fund, the Primary Care Development Corporation, and the Milbank Memorial Fund.

Virginia

Coalition to Set Primary Care Spending Target Starting in 2026

In early 2020, several factors prompted the Virginia Center for Health Innovation (VCHI), a nonprofit, nonpartisan health sector convener, to prioritize helping the state build the infrastructure necessary to facilitate sustainable primary care payment models. During the early days of the pandemic, concerns that primary care practices might have insufficient revenue or reserves to maintain their operations created an opportunity to act. Another springboard, says Beth A. Bortz, president and CEO of VCHI, was that “[w]e had this unusual moment in time where almost every national leader in primary care happened to be a Virginian,” including presidents of the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Board of Family Medicine, and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. “I thought, if not now, when?”

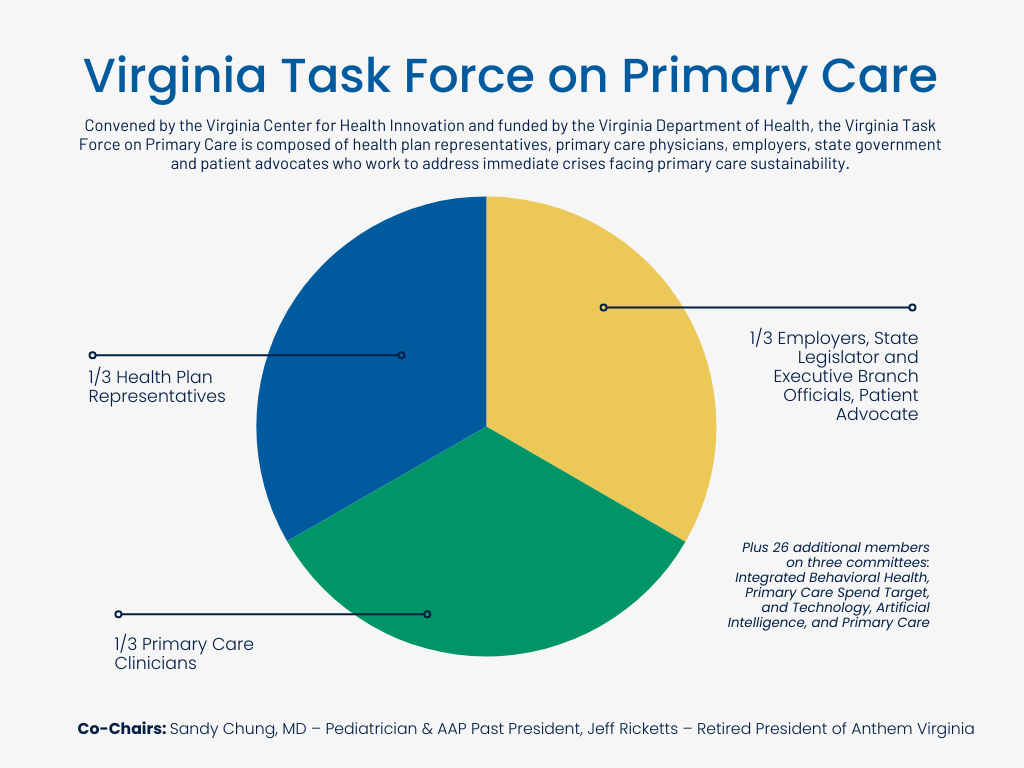

With the support of these leaders and nearly $300,000 in seed funding from Arnold Ventures, VCHI launched the Virginia Task Force on Primary Care in August 2020, bringing together health care stakeholders across Virginia to address immediate crises facing primary care. It now receives more than $800,000 annually from the Virginia Department of Health.

The task force’s early focus has been on developing better data platforms to track and improve primary care performance metrics and support accountability within the health care system. Metrics include immunization data and a person-centered primary care measure. “It became apparent as we were getting underway that we did not have good data about the state of primary care in the Commonwealth of Virginia,” Bortz explains.

For the last two years, the task force has released the Virginia Primary Care Scorecard, an annual tracking tool developed by VCHI that reports on the state’s primary care investment, regional clinician capacity, primary care utilization, primary-care-related outcomes, and patient access to primary care. Critically, the scorecard enables Virginia’s performance to be compared with national benchmarks. Other reports describe trends such as spending for primary care, behavioral health, and telehealth, as well as total cost of care. Additionally, a Primary Care Scorecard Dashboard has been released in parallel to enable interactive exploration of the scorecard data. This dashboard was further refined in 2024 to provide information on the patient experience at the county level, enabling legislators and others to better understand the needs in specific regions.

The scorecards show that there are primary care provider shortages across the state, says Lauryn Walker, PhD, RN, chief strategy officer at VCHI.

“It’s really not an urban/rural issue. This is an everybody issue.”

However, there is regional variation in provider types. For example, in southwestern Virginia’s Appalachia region, the most rural part of the state, primary care is predominantly delivered by nurse practitioners without support from physicians, whereas in eastern Virginia’s more populated Tidewater area, physicians are more common but there are few advanced practice providers.

The task force has held off on reaching a consensus definition of primary care services, a necessary step to set a state spending target. Instead, the group has taken actions that led to “small wins,” which have kept its members engaged and built trust. These actions include distributing 750,000 pieces of personal protective equipment to frontline primary care providers and presenting preliminary primary spending data at the January 2022 session of the Virginia General Assembly to successfully advocate for a $151 million increase in Medicaid payments for primary care services, from 70% to 80% of Medicare rates.

As the task force moves toward its 2025 goals, which include developing a primary care spending threshold target along with an enforcement mechanism to recommend to the state’s General Assembly in 2026, Bortz anticipates that “there is going to be increased scrutiny on the methodology.” Currently, the task force uses a four quadrant approach that allows comparisons based on both narrow and broad definitions of primary care providers and services. In 2024, the scorecard reported that Virginia spent 2.3% to 4.1% of the state’s total health care dollars on primary care services.

Though VCHI wants to engage health care purchasers in their primary care improvement efforts, the state’s smaller employers do not have the purchasing scale to influence health plan design, and its larger employers tend to be national in scope and unlikely to tailor programs to meet Virginia-specific goals. This currently leaves health plans as the pressure point for action. “Our plan partners are very much motivated to ensure that there is sustainable primary care,” says Bortz.

“[Payers] recognize that primary care is some of the best value in the health care system and they definitely want to make sure that people have access to primary care. But translating that into how they spend more, that’s the difficult question and we’re working on it.”

Connecticut

Primary Care Spending, Quality, and Cost Growth Targets to Drive Improved Outcomes and Affordability

Connecticut’s 10% primary care spending target for commercial health plans, Medicare, and Medicaid was established by Governor Ned Lamont in 2020 through an executive order and then codified into legislation by the Connecticut General Assembly in 2022. “The primary care spending target came into being as the state was beginning to look at value-based payments, population health, and alternative payment models more broadly,” says Lisa P. Sementilli, a lead planning analyst in the Connecticut Office of Health Strategy (OHS).

“Importantly, the primary care spending target was passed and enacted as part of a package with a cost growth target, which is a total cost of care target, and quality benchmarks.”

Equity was also a driver. The state’s primary care workforce, with 148 primary care clinicians per 100,000 people in 2021, was higher than the nationwide average of 112 primary care clinicians per 100,000 people. But, based on data from 2016 to 2021, this number drops to 103 primary care clinicians per 100,000 people in socially and economically disadvantaged areas. Also, in 2022, compared with White residents, Hispanic residents were five times more likely and Black residents were twice as likely to report not having a personal doctor.

“Connecticut is a state that has disparities in access,” says Alex Reger, PhD, director of the Healthcare Benchmark Initiative at OHS. His office is working with the Connecticut Primary Care Office to better understand the variation in provider availability in different communities across the state, as well as the insurance that these providers accept and the facilities in which their services are offered.

Health care cost growth, primary care spending, and quality targest form the three legs of the Healthcare Benchmark Initiative. Together, they reflect Connecticut’s long-term strategy of improving quality and outcomes for all while rebalancing health spending toward primary care services and making health care more affordable.

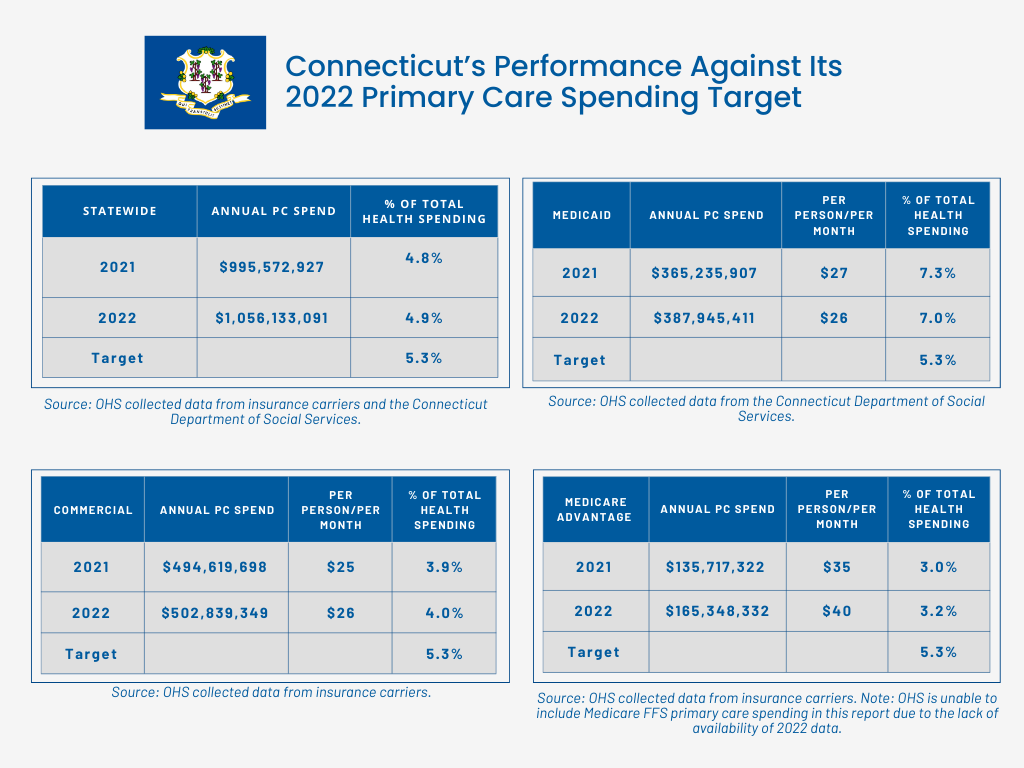

So far, however, the state has not met its primary care spending target. The state calculates primary care spending as all claims expenditures for physicians (MDs and DOs) practicing geriatric medicine (when practicing primary care), family medicine, internal medicine (when practicing primary care), and pediatric and adolescent medicine, as well as for nurse practitioners and physician assistants (when practicing primary care). Statewide primary care spending was 4.8% in 2021 against a target of 5.0%; it increased to 4.9% in 2022 against a target of 5.3%. Data for 2023, against a target of 6.9%, will be released in March 2025; the target increases to 8.5% for 2024 and 10% for 2025.

“We’re not as close as we should be to the target,” Reger says.

Though there is much work to be done, “one of the most important things that the primary care spending target does is start the conversation. Everyone comes to the table to talk about access, equity, workforce needs… And then we are trying to make the data as public and transparent as possible so that that conversation can be truly robust.”

To date, the data has highlighted the Medicaid program’s larger investment in primary care, compared with that of the commercial and Medicare markets. In 2022, Connecticut’s Medicaid market allocated 7% of total health care spending to primary care; that same year, primary care spending accounted for only 3.2% of total health care provided by Medicare Advantage health plans and 4% of total health care provided by the commercial market. This reflects both the Medicaid program’s more developed primary care infrastructure and the effects that insurer incentives can have on access.

There are currently no enforcement mechanisms or incentives for insurers to meet the primary care spending benchmark. However, that might change through Connecticut’s participation in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services States Advancing All-Payer Health Equity Approaches and Development (AHEAD) Model, which began in July 2024. Building on state-based models, including those in Vermont, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, AHEAD aims to rebalance states’ health care delivery toward primary care. One way it will do so is by holding states accountable for cost growth and primary care investment targets in addition to population health and health equity outcomes.

California

15% Primary Care Spending by 2034

California is often considered a policy leader on health coverage, having recently expanded Medicaid to undocumented adults and children. But its health care costs are high, and when it comes to the state’s provision of primary care, “we perform in the bottom quartile of states for a whole range of measures,” says Kathryn E. Phillips, MPH, associate director of Improving Access at the California Health Care Foundation (CHCF). Currently, 11.4 million Californians — more than one-quarter of the state’s population — live in a federally designated primary care shortage area.

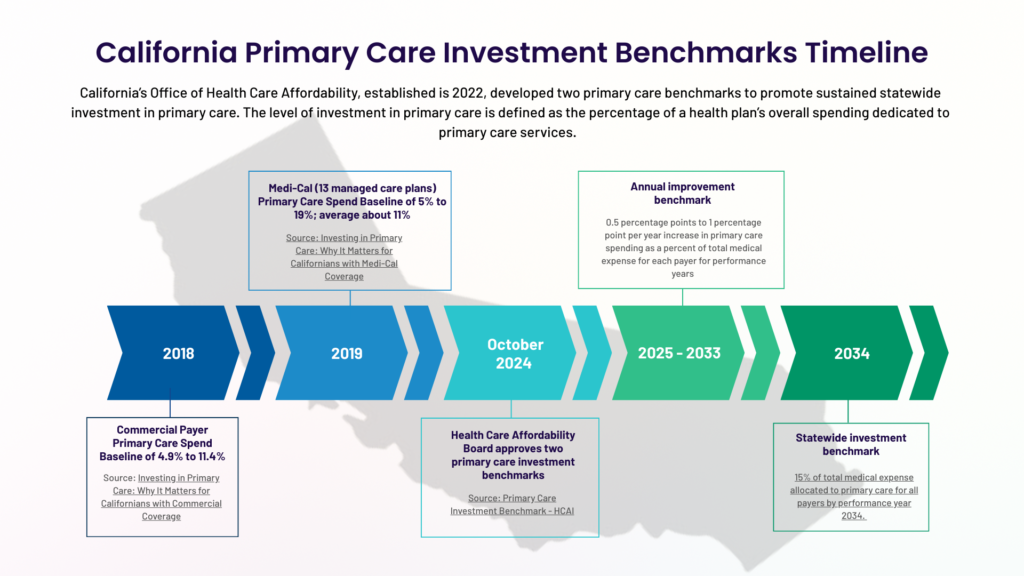

In 2022, the California legislature responded to a coalition of consumer advocacy groups, like Health Access California, as well as organized labor and other stakeholders, which were collectively calling for more affordable care, by creating an Office of Health Care Affordability. With the goal of lowering spending while improving health outcomes, its board, in October 2024, approved a benchmark of 15% investment in primary care by 2034 for all health care payers. It also set a related, annual improvement benchmark of a 0.5% to 1% increase in primary care spending as a percentage of total health care spending through 2033.

The benchmark, says Phillips, is ambitious but achievable. “It will be harder for some [health] plans than others, but we do think that is possible for everyone,” she adds. California defined primary care to include the services of doctors, nurses, and pharmacists. Obstetrician gynecologists, who sometimes provide both primary care and specialty care to women, and naturopathic providers were excluded.

About six months prior to setting the primary care spending targets, the Office of Health Care Affordability’s board approved an annual target of 3.5% on statewide health care spending, with a goal of 3% by 2029. The office is expected to set a target for behavioral health investment next year.

Support for establishing these benchmarks grew from foundational work by the California Health Care Foundation. In 2019, the nonprofit organization commissioned three reports: two assessed primary care spending in the state’s commercial and Medi-Cal markets (discussed below), and the third, Investing in Primary Care: Lessons from State-Based Efforts, summarized transparency, contracting, and regulatory approaches that other states had used to increase investment in primary care.

We found broad support for primary care in our state, but no one named primary care as their number one priority,” Phillips says. “And yet, often the top priority – such as more affordable care or better access to behavioral health services – relies on a strong foundation of primary care.

Recognizing the collective power of the state’s large public and private health care purchasers, CHCF convened the Primary Care Investment Coordinating Group of California in 2021. For the last four years, purchasers have been working alongside researchers, consumer advocates, and policymakers to assess the available data and identify effective mechanisms to elevate primary care in California. Their recommended actions include the following: to measure and report on primary care spending; to set a target for primary care spending as a percentage of total medical care expenditures; to adopt payment models that advance primary care; to establish purchaser requirements to evaluate benefits and provider networks for inclusion of primary care clinicians; and to track the outcomes of increased primary care spending. Most of these have since been adopted by the Office of Health Care Affordability.

Currently, there is a wide — and unwarranted — variability in primary care spending across populations and payer types, according to the CHCF. Its baseline report, Investing in Primary Care: Why It Matters for Californians with Commercial Coverage, found that, in 2018, the average adjusted primary care spending percentage ranged from 4.9% to 11.4% among the health plans serving 13.9 million commercially insured adults in California. Also, among the 13 Medi-Cal managed care plans that participated in CHCF’s Investing in Primary Care: Why It Matters for Californians with Medi-Cal Coverage report, the average adjusted primary care spending percentage ranged from 5% to 19%, averaging about 11% in 2019.

While California’s primary care spending benchmarks are not enforceable, their design includes incentives to encourage health plans to meet them. The public reporting of health plan spending data that the state now collects is anticipated to motivate change. Additionally, the Office of Health Care Affordability can choose not to apply enforcement measures to health plans that achieve primary care or behavioral health spending goals yet exceed the 3.5% cost containment threshold.

Parallel to these benchmarking efforts, the state has been working over the last few years to increase investments in its primary care and behavioral health workforce. This includes expanding primary care and psychiatry residency slots, opening new medical schools to train more physicians, supporting nurse practitioners to become psychiatric and mental health nurse practitioners, and offering loan repayment and scholarships. Other initiatives focus on increasing workforce diversity through programs that promote the success of first-generation college students and people of color in nursing, medical, and pharmacy schools.

Oklahoma

Leveraging the State’s Transition to Medicaid Managed Care to Implement an 11% Primary Care Spending Target

Oklahoma’s primary care spending target was approved by the legislature in 2022 as part of the state’s Ensuring Access to Medicaid Act. This legislation directed the Oklahoma Health Care Authority (OHCA), the agency that manages the state’s Medicaid program, to transition a portion (about 50%) of the state’s Medicaid enrollees from a traditional fee-for-service plan, SoonerCare, to a managed care model, SoonerSelect. Separate legislation adopted in 2022 allowed OHCA to implement an incentive program to encourage contracted providers to offer preventive and primary care services and to increase supplemental payments to hospitals.

State leaders designed SoonerSelect, which launched on April 1, 2024, to increase access and improve quality of care through health plan performance measures focused on social determinants of health, diabetes, and childhood obesity. The managed care program covers non-disabled children, including children in foster care, low-income parents, pregnant women, and non-disabled adults ages 19-64. (Additionally, eligible American Indian/Alaskan Native members can choose to opt in.) OHCA has directed the three health plans administering the program to implement care coordination strategies that incentivize and encourage primary care, reduce unnecessary emergency room visits by investing in early preventive treatment, and expand the primary care provider and specialist networks. They also offer members “value-added” benefits, such as monetary incentives for attending well-child and annual primary care visits.

Aligned with SoonerSelect’s quality strategy, the new incentive program aims to enhance primary care by increasing payments to providers for preventive and primary care services including prenatal visits, vaccinations, behavioral health screenings, after-hours access to services, and well visits. In November 2024, physicians, advanced practice nurses, mid-level practitioners, behavioral health providers, and other qualifying providers received more than $11.5 million of a total $134 million anticipated over the program’s first 15 months. They have since received an additional $37.5 million, totaling $49 million in enhanced payments.

The state’s shift to managed care was driven both by the need to manage the health of its growing Medicaid population, which has grown by more than 330,000 enrollees since voters approved a ballot measure to add Medicaid expansion to the state’s constitution, and by the desire to improve Oklahoma’s poor health ranking. “The state saw an opportunity to increase access to primary care and really encourage preventive services,” explains Christina Foss, OHCA chief of staff.

Currently, Oklahoma’s Medicaid program spends 5% of its health care budget on primary care, less than half of the 11% target to be reached within four years of SoonerSelect’s launch. “We have some work to do,” says Foss. “The primary care spend initiative, in conjunction with the new dollars coming to the state through the directed payment programs, like the provider incentive payment, is hopefully going to create some opportunities for providers and the [health] plans,” she adds. The primary care spending target does not apply to the state’s other health plans.

A Quality Advisory Committee, established as part of the 2022 legislation to oversee and evaluate quality-related aspects of the program, is responsible for defining primary care and developing a methodology for determining primary care spending. After the committee, which includes providers, researchers, and health system leaders, finalizes the state’s primary care spending algorithm, it will available on OHCA’s website. This public dashboard will enable people to “click through different counties and see what the primary care spend is there, even by provider type,” says Foss.

In addition to its partnership with providers, the state’s Member Advisory Task Force, which was originally formed in 2007 to provide member and family feedback, has been “incredibly helpful in trying to formulate a plan that that can work for Oklahoma,” she says.

“We’re trying to determine what models we can help facilitate regionally. They might look different in certain areas of the state than others.” — Christina Foss

Rhode Island

Rethinking Its Legacy Standards Based on Current Data

When Rhode Island established a primary care expenditure target for commercial health insurers in 2010, it was the first state to do so. The Office of the Health Insurance Commissioner (OHIC), which, unique to the state, oversees prior approval health insurance rate review, mandated an increase of 1% annually to reach a target of 10.7% by 2014. This goal was double its baseline primary care spending of 5% of the health care dollar, and OHIC has required health plans to maintain that level since 2015. “I would characterize that first period, from 2010 to 2014, as successful because we did actually increase funding for primary care and we did increase from zero to over 100 practices that were considered medical homes,” says Cory King, who became the Rhode Island Health Insurance Commissioner in April 2024 after serving as acting commissioner for more than a year.

But in early 2023, a news article highlighting the experience of a retired Rhode Island physician who was unable to find a primary care doctor motivated King to review the recent literature and meet with providers in the state to understand how the system was failing even doctors, “the ultimate insiders,” he says. King also wanted to learn more about the experiences of states that had developed primary care spending targets in the years after Rhode Island’s early implementation. OHIC collaborated with a group of New England states to develop a “common set of specifications to apply to claims data” and accurately identify primary care service payments. It then evaluated the state’s commercial health plan data using both approaches.“Under the legacy definition, our primary care spending was over 10%,” King says. “But when you looked at the new definitions, it was around 6%.”

“The old way we were doing it was innovative but broken, and we needed to recast and recalibrate our approach,” explains King. There are several reasons for this difference, he says. In the numerator of the primary care spending equation, the definition of primary care included different qualifying services. Rhode Island’s legacy definition included some of the insurers’ Medicare Advantage and/or Medicaid payments for patient-centered medical homes. Additionally, in the denominator, payments to out-of-state providers were not included in the calculation, an exclusion that meant the total cost of care did not fully reflect the state’s costs because patients are more likely to travel to neighboring states for specialty care.

Legacy Primary Care Expenditure Definition, Established in 2010. The amount that an insurer spends on payments to primary care providers (i.e., the physician, practice, or other medical provider considered by the insured to be his or her usual source of medical care, such as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and physician associates, but excluding specialty providers) and other preventive and basic health services plus non-fee-for-service investments, including health information technology, patient-centered medical homes, web-based data sharing (CurrentCare), provider incentives, training physician loan forgiveness, and flu clinics. Primary care spending was calculated by dividing this amount by total health care spending on Rhode Island providers.

New Primary Care Expenditure Definition, Effective March 20, 2025 Primary care expenditures means all claims-based and non-claims-based payments by the health insurer directly to a primary care practice or integrated system of care for primary care services delivered to Rhode Island residents at a primary care site (excluding urgent care centers and retail pharmacy clinics). This includes claims-based payments for primary care services (defined using a set of taxonomy codes) and non-claims-based payments for capitated and prospective contracts, provider incentives, population health management, primary care practice infrastructure, primary care provider salaries, recouped payments due to reviews, audits, or investigations, and patient-centered medical home administrative expenses. Primary care spending is calculated by dividing this amount by total spending on all health care providers.

“This is an opportunity to improve our measurements and do so in a way that I think will generate additional investments in primary care without having to go through some other mechanism.”

In December 2023, OHIC published a report, Primary Care in Rhode Island: Current Status and Policy Recommendations, summarizing its review of national and local primary care trends, the literature on primary care’s contribution to health outcomes, and interviews with local providers and practice groups, insurers, and others. Based on the report’s recommendations, OHIC completed a regulatory and cost-benefit analysis of proposed amendments to its policies, including a new primary care expenditure target of 10%, in September 2024.

While this new goal is lower than the legacy target of 10.7%, the 1% indirect funding to support the state’s health information exchange will no longer count toward the target as it is not direct spending on primary care. Additionally, to truly reflect the state’s total cost of health care, OHIC will include payments for all providers, including physicians and others practicing outside of Rhode Island. This change is expected to increase the state’s measurement of its commercial total health care costs by about $190 million.

King says that based on his calculations, promulgating these rules will double the current per-member-per-month investment in primary care. OHIC also plans to implement strategies that incentivize increases to the provider fee schedule and reduce administrative burden on primary care practices.

To date, there have been only a handful of cases where commercial health insurers did not meet the state’s primary care expenditure target. “We’ve never had to take an enforcement action,” says King. Instead, OHIC has worked with these health plans to establish a plan to address their funding shortfalls. The office will continue to rely on insurer-reported data, but will use new data collection processes from its all-payer claims database to ensure the numbers align. “I plan to leverage our examination authority to perform periodic audits of insurance companies’ filings to us,” he says.

While King, like other state leaders involved in enhancing primary care, would like to see more leadership at the national level, he pointed to the AHEAD Model as a step in the right direction. “AHEAD has at its core primary care investment targets for traditional Medicare and for all payer[s],” he says. “So that is the federal government, through an innovation program, saying, ‘let’s do it.’”